Introduction

Abstract¶

Magnetic resonance imaging has progressed significantly with the introduction of advanced computational methods and novel imaging techniques, but their wider adoption hinges on their reproducibility. This concise review synthesizes reproducible research insights from recent MRI articles to examine the current state of reproducibility in neuroimaging, highlighting key trends and challenges. It also provides a custom GPT model, designed specifically for aiding in an automated analysis and synthesis of information pertaining to the reproducibility insights associated with the articles at the core of this review.

1Introduction¶

Reproducibility is a cornerstone of scientific inquiry, particularly relevant for data-intensive and computationally demanding fields of research, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) Stikov et al., 2019. Ensuring reproducibility thus poses a unique set of challenges and necessitates the diligent application of methods that foster transparency, verification, and interoperability of research findings.

While numerous articles have addressed the reproducibility of clinical MRI studies, few have looked at the reproducibility of the MRI methodology underpinning these studies. This is understandable given that the MRI development community is smaller, driven by engineers and physicists, with modest representation from clinicians and statisticians.

However, performing a thorough meta-analysis or a systematic review of these studies in the context of reproducibility presents challenges due to:

- i) the diversity in study designs across various MRI development subfields, and

- ii) the absence of standardized statistics to gauge reproducibility performance.

With this mini-review we aim to examine the current landscape of reproducible research practices across various MRI studies, drawing attention to common strategies, tools, and repositories used to achieve reproducible outcomes. We anticipate that this approach provides a living review that can be automatically updated to accommodate the continuously expanding breadth of methodologies, helping us identify commonalities and discrepancies across studies.

2Methodology¶

In distilling reproducibility insights powered by GPT, this review centered on 31 research articles published in the journal Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (MRM), chosen by the editor for their dedication to enhancing reproducibility in MRI. Since 2020, the journal has published interviews with authors of these selected publications, discussing the tools and practices they used to bolster the reproducibility of their findings (available here).

2.1Mapping selected articles in the semantic landscape of reproducibility¶

We performed a literature search to identify where these studies fall in the broader literature of reproducible neuroimaging. To retrieve articles dedicated to reproducibility in MRI, we utilized the Semantics Scholar API [2] with the following query terms on November 23, 2023:

(code | data | open-source | github | jupyter ) & ((MRI & brain) | (MRI neuroimaging)) & reproducib~.Among 1098 articles included in the Semantic Scholar records, SPECTER vector embeddings Cohan et al., 2020 were available for 612 articles, representing the semantics of publicly accessible content in abstracts and titles. For these articles, the high-dimensional semantic information captured by the word embeddings was visualized using UMAP McInnes et al., 2018 Figure 1. This visualization allowed the inspection of the semantic clustering of the articles, facilitating a deeper understanding of their contextual placement within the reproducibility landscape. In addition, the following diagram illustrates the hierarchical clustering of the selected studies in the broader literature:

2.2Creating a knowledge base for a custom GPT¶

We created a custom GPT model, designed specifically to assist in the analysis and synthesis of information pertaining to the 31 reproducible research insights. The knowledge base of this retrieval-augmented generation framework incorporates GPT-4 summaries of the abstracts from 31 MRM articles, merged with their respective MRM Highlights interviews, as well as the titles and keywords associated with each article (refer to Appendix A). This compilation was assembled via API calls to OpenAI on November 23, 2023, using the gpt-4-1106-preview model.

This specialized GPT, named RRInsights, is tailored to process and interpret the provided data in the context of reproducibility, for the system prompts please see Appendix B.

3Results¶

3.1Contextual placement of the selected articles in the landscape of reproducibility¶

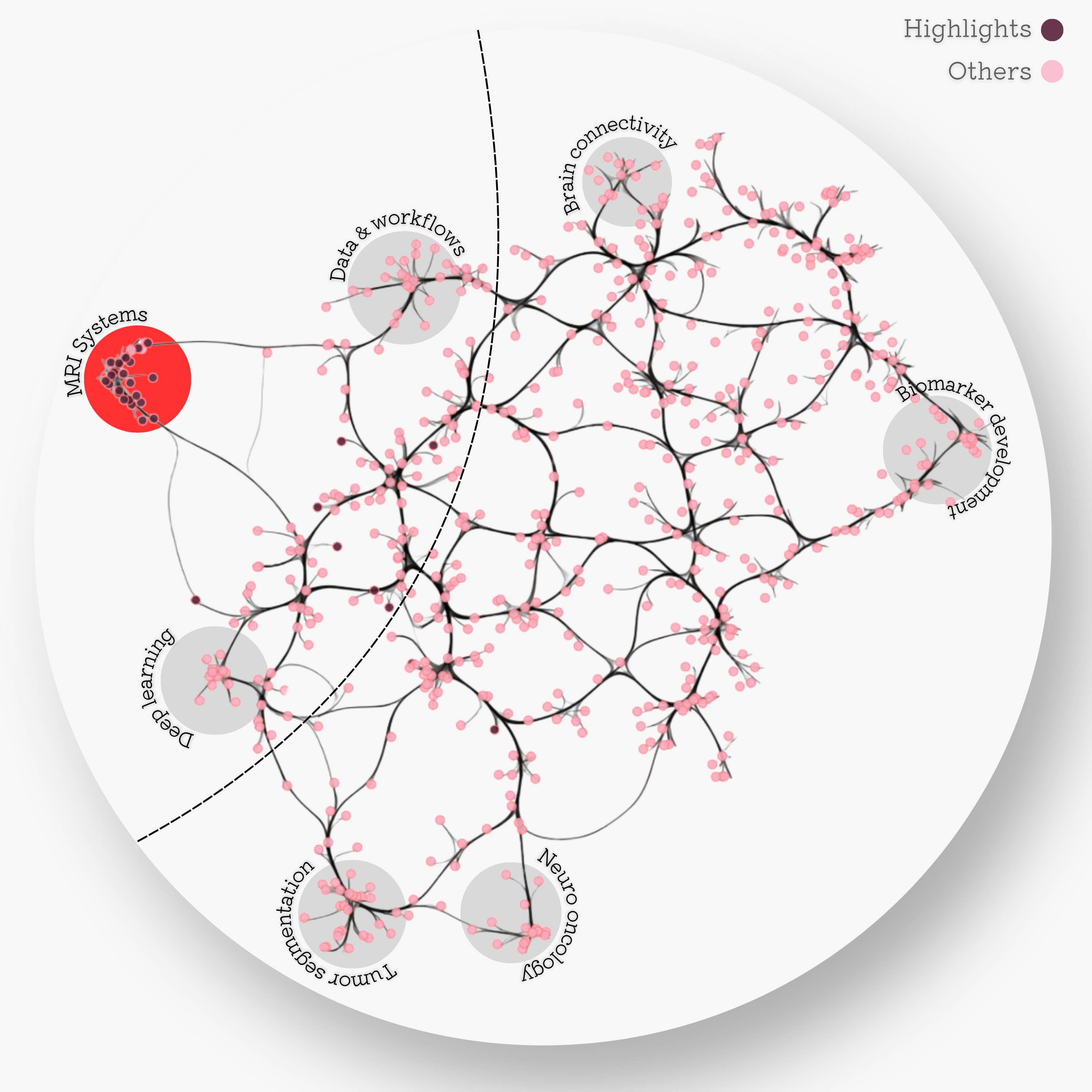

The MRI systems cluster was predominantly composed of articles published in MRM, with only two publications appearing in a different journal Adebimpe et al., 2022Tilea et al., 2009. Additionally, this cluster was sufficiently distinct from the rest of the reproducibility literature, as can be seen by the location of the dark red dots Figure 2. Few other selected articles (8/31) were found at the intersection of the MRI systems, deep learning, and data/workflows clusters, which in total spans 103 articles. Since the custom GPT model was trained on the 31 selected MRM articles (red dots), Figure 2 serves as a map for inferring the topics where RRInsights is more likely to be context-aware.

Click here to see the static version of the SAKURA plot

Figure 2:Edge-bundled connectivity of the 612 articles identified by the literature search. A notable cluster is formed by most of the MRM articles that were featured in the reproducible research insights (purple nodes), particularly in the development of MRI systems. Few other selected articles fell at the intersection of MRI systems, deep learning, and workflows. Notable clusters for other studies (pink) are annotated by gray circles.

Click here to see 3D UMAP scatter

Figure 3:Edge-bundled connectivity of the 612 articles identified by the literature search. A notable cluster is formed by most of the MRM articles that were featured in the reproducible research insights (purple nodes), particularly in the development of MRI systems. Few other selected articles fell at the intersection of MRI systems, deep learning, and workflows. Notable clusters for other studies (pink) are annotated by gray circles.

3.2Custom GPT for reproducibility insights¶

Through its advanced natural language processing capabilities, RRInsights can efficiently analyze the scoped literature, extract key insights, and generate comprehensive overviews of the research papers focusing on MRI technology. The custom GPT is available at https://

API key not found. Available dataset will be used. Example:

[{'role': 'system', 'content': 'You are a helpful assistant designed to understand and summarize the reproducibility aspects of neuroimaging research articles.'}, {'role': 'user', 'content': 'The following content is from ARTICLE 1. In relavance to its title and abstract, create 4 keywords, then summarize what did the study achieve and why it was reproducible in 4 sentences: Title: In vivo magnetic resonance 31P‐Spectral Analysis With Neural Networks: 31P‐SPAWNN \nAbstract: We have introduced an artificial intelligence framework, 31P‐SPAWNN, in order to fully analyze phosphorus‐31 ( 31$$ {}^{31} $$ P) magnetic resonance spectra. The flexibility and speed of the technique rival traditional least‐square fitting methods, with the performance of the two approaches, are compared in this work. \nReproducibility Insights:\nGeneral questions\nQuestions about the specific reproducible research habit\n\nThis MRM Reproducible Research Insights interview is with Julien Songeon and Antoine Klauser from the University of Geneva in Switzerland, respectively first and last author of a paper entitled “In vivo magnetic resonance 31 P-Spectral Analysis With Neural Networks: 31P-SPAWNN”. This work was singled out because it demonstrated exemplary reproducible research practices; specifically, the authorsshared the source code for their proposed method (simulations, their deep learning network, and sample datasets).\nTo learn more, check outour recent MRM Highlights Q&A interview with Julien Songeon and Antoine Klauser.\n1. Why did you choose to share your code/data?\nThis approach naturally facilitates the demonstration presented in the manuscript, allowing interested readers to test the method themselves. Also, we enable others to validate and reproduce our results effectively.\nAlso, rather than adopting a competitive approach, we prefer, in this way, to promote collaboration in MR research, because a collaborative mindset can foster advancements and progress in the field. Ultimately, code sharing can assist other researchers who wish to pursue similar research directions. They can utilize our work as a foundation, potentially saving significant implementation and coding efforts. This accelerates the pace of research and encourages researchers to build upon existing knowledge rather than wasting resources on replication efforts.\n2. What is your lab or institutional policy on sharing research code and data?\nOur institution has a highly flexible policy regarding the sharing of code and data. While open science practices are strongly encouraged, there are no clear advantages for us nor mandatory constraints in place that require us to share .\n3. How do you think we might encourage researchers in the MRI community to contribute more open-source content along with their research papers?\nI believe that if code and data sharing were recognized to add clear value to a submitted manuscript, then authors would have a positive incentive to provide open-source content. In addition to evaluating factors such as innovation, soundness of methodology, quality of results, and clarity of demonstration, editors should acknowledge the inclusion of code and data as a valuable contribution to the scientific community.\n1. Your code repository is really well documented. What advice would you give to people preparing to share their first repository?\nWhen preparing to share a code repository, you need to think about the future users of your code and what information they will need to understand and use it effectively. The README file should explain the purpose of the code, and provide installation instructions, dependencies, and examples. The files could have comments within the code to clarify specific sections or functions. To help users navigate the repository and locate relevant files easily, I suggest organizing your code and files in a logical manner, using explicit naming. Finally, I would recommend including examples and/or tutorials, providing sample input data and scripts that demonstrate how to use your code. This can really help users to understand the expected workflow and apply the code to their own research.\n2. What questions did you ask yourselves while you were developing the code that would eventually be shared?\nIn the development phase, we aimed to create code that could be easily adapted and reused for different experiments or in different research scenarios.We also considered the computational complexity and performance of our code to ensure that it could handle large training datasets or complex computations effectively.Finally, we paid attention to the clarity and comprehensibility of our code. We aimed to write code that would be accessible to other researchers.\n3. How do you recommend that people use the project repository you shared?\nStart with the README file. Read the README file and try to rerun the command shown. it will provide an overview of the capability and usage of the code and model.Once you have a good understanding of the code, try to run it on your own data, adapting the number of points and the bandwidth and retraining a new model.Then, further adaptation could be implemented: you could add other metabolites, apply the method to other nuclei, explore other model architectures.\n4. Are there any other reproducible research habits that you didn’t use for this paper but might be interested in trying in the future?\nUsing tools likeDockerorSingularityto create reproducible and portable computing environments. This ensures that the code can be executed consistently across different systems and configurations without cumbersome installation or setup. In addition, keeping track of and archiving the successive versions of the code in a systematic manner allows researchers to easily track and manage changes to the code over time. This can be particularly useful when code is linked to a publication and extra data are required during the peer-review process. Also, we could try making automated pipelines that capture the entire workflow, from data acquisition to final results. Doing this simplifies the reproducibility process and reduces the potential for human error.\n'}, {'role': 'assistant', 'content': 'Keywords: 31P‐SPAWNN, neural networks, reproducibility, magnetic resonance spectroscopy\n\nStudy Achievements and Reproducibility Summary:\n\n1. The study introduced a new artificial intelligence framework, 31P‐SPAWNN, for analyzing 31P magnetic resonance spectra, demonstrating that it provides a fast and flexible alternative to traditional least-square fitting methods.\n2. Reproducibility was exemplary as the authors shared the source code, simulations, their deep learning network, and sample datasets, enabling other researchers to test, validate, and reproduce their results easily.\n3. Open sharing of the code and data was motivated by a commitment to collaborative advancement in MR research and the drive to facilitate incremental knowledge growth within the community without redundant effort.\n4. The authors suggest best practices for sharing research repositories, including comprehensive documentation, logical organization, and the use of tools like Docker or Singularity to improve the portability and consistency of the computational research environment, thereby enhancing reproducibility further.'}]

Automated interaction with GPT4, iterating over all (31) seleted records

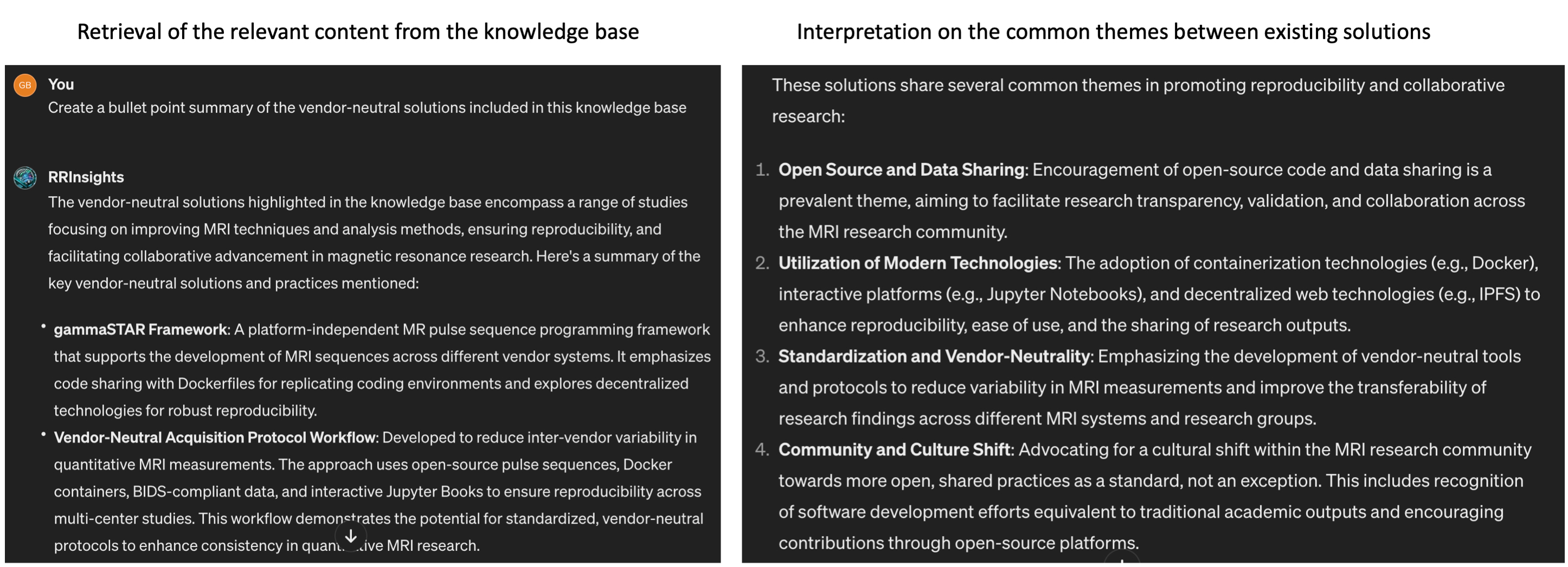

Figure 5:An example user interaction with the RRInsights custom GPT. The model is capable of fetching the studies concerned with the requested content (i.e., vendor-neutral solutions and provide summaries highlighting thematic similarities between them, particularly focusing on reproducibility aspects.

Figure 5 presents an example interaction with RRInsights to create a summary about the vendor-neutral solutions found in the knowledge base. The model’s response to this inquiry demonstrates that RRInsights is context-aware, adept at pinpointing relevant information in the knowledge base, and offering interpretations within the framework of reproducibility.

Figure 6:T-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) visualization of GPT summary word embeddings, generated using the OpenAI text-embedding-ada-002 model. Each marker represents one of 31 selected MRM articles.

3.2.1GPT-powered summary of the reproducible magnetic resonance neuroimaging¶

Most MRI development is done on commercial systems using proprietary hardware and software. Peeking inside the black boxes that generate the images is non-trivial, but it is essential for promoting reproducibility in MRI.

Quantitative MRI articles are powerful showcases of reproducible research practices, as they usually come with fitting models that can be shared on public code repositories. The applications range from MR spectroscopy [7–10] to ASL [11], diffusion MRI [12,13], CEST [14], magnetization transfer [15–17], B1 mapping [18] and relaxometry [16–20].

Transparent reconstruction and analysis pipelines are also prominently featured in the reproducible research insights, including methods for real-time MRI [21], parallel imaging [22], large-scale volumetric dynamic imaging [23], pharmacokinetic modeling of DCE-MRI [24], phase unwrapping [25], hyperpolarized MRI [26], Dixon imaging [27] and X-nuclei imaging [28]. Deep learning is increasingly present in the reproducibility conversation, as MRI researchers are trying to shine a light on AI-driven workflows for phase-focused applications [29], CEST [14], diffusion-weighted imaging [30], myelin water imaging [18], B1 estimation [31], and tissue segmentation [32].

Reproducibility of MRI hardware is still in its infancy, but a recent study integrated RF coils with commercial field cameras for ultrahigh-field MRI, exemplifying the coupling of hardware advancements with software solutions. The authors shared the design CAD files, performance data, and image reconstruction code, ensuring that hardware innovations can be reproduced and utilized by other researchers [33].

Finally, vendor-neutral pulse sequences are putting interoperability and transparency at the center of the reproducibility landscape. Pulseq and gammaSTAR are vendor-neutral platforms enabling the creation of MRI pulse sequences that are compatible with three major MRI vendors [34][[35]. In addition, VENUS is an end-to-end vendor-neutral workflow that was shown to reduce inter-vendor variability in quantitative MRI measurements of myelin, thereby strengthening the reproducibility of quantitative MRI research and facilitating multicenter clinical trials [36,37].

3.2.1.1Data sharing¶

There is a growing number of studies providing access to raw imaging data, pre-processing pipelines, and post-analysis results. Repositories like Zenodo, XNAT, and the Open Science Framework (OSF) serve as vital resources for housing and curating MRI data. Data sharing is also made easier thanks to unified data representations, such as the ISMRM raw data format [38] for standardizing k-space data, and the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) for organizing complex datasets [39] and their derivatives [40].

3.2.1.2Code sharing¶

Software repositories such as GitHub and GitLab are making it easier to centralize processing routines and to adopt version control, unit tests and other robust software development practices. The introduction of tools for automated QA processes, as seen in the development of platforms like PreQual for DWI analysis [12], signifies an emphasis on interoperability and standardization.

The increasing adoption of containerization and virtual environments makes workflows transparent and easy to execute. Tools like Docker and Singularity are used to package computing environments, making them portable and reproducible across different systems. Studies employing these tools enable MRI researchers to replicate computational processing pipelines without dealing with dependency issues in local computational environments [32,35,36].

The rise of machine learning and artificial intelligence in MRI necessitates rigorous evaluation to ensure reproducibility. Studies that use deep learning are beginning to supplement their methodological descriptions with the open-source code, trained models, and simulation tools that underpin their algorithms. Algorithms such as DeepCEST, developed for B1 inhomogeneity correction at 7T, showcase how clinical research can be improved by reproducible research practices [14]. Sharing these algorithms allows others to perform direct comparisons and apply them to new datasets.

3.2.1.3Vendor-neutrality¶

Finally, pulse-sequence and hardware descriptions are slowly entering the public domain [33–36]. For a long time MRI vendors have been reluctant to open up their systems [41], but standardized phantoms [42] are creating benchmarks that require transparency and reproducibility. This is particularly relevant for quantitative MRI applications, where scanner upgrades and variabilities across sites are a major hurdle to wider clinical adoption [43–45].

3.2.1.4Dissemination¶

Reproducibility is also bolstered by interactive documentation and tools such as Jupyter Notebooks, allowing for dynamic presentation and hands-on engagement with data and methods. Platforms incorporating such interactive elements are being utilized with greater frequency, providing real-time demonstration of analysis techniques and enabling peer-led validation. Resources such as MRHub, MRPub, [Open Source Imaging] (https://

4Discussion and Future Directions¶

The progress towards reproducibility in MRI research points to a distinct cultural shift in the scientific community. The move towards open-access publishing, code-sharing platforms, and data repositories reflects a concerted effort to uphold the reproducibility of complex imaging studies. Adopting containerization technologies, pushing for standardization, and consistently focusing on quality assurance are key drivers that will continue to improve reproducibility standards in MRI research.

<wordcloud.wordcloud.WordCloud at 0x756a69f9c370>

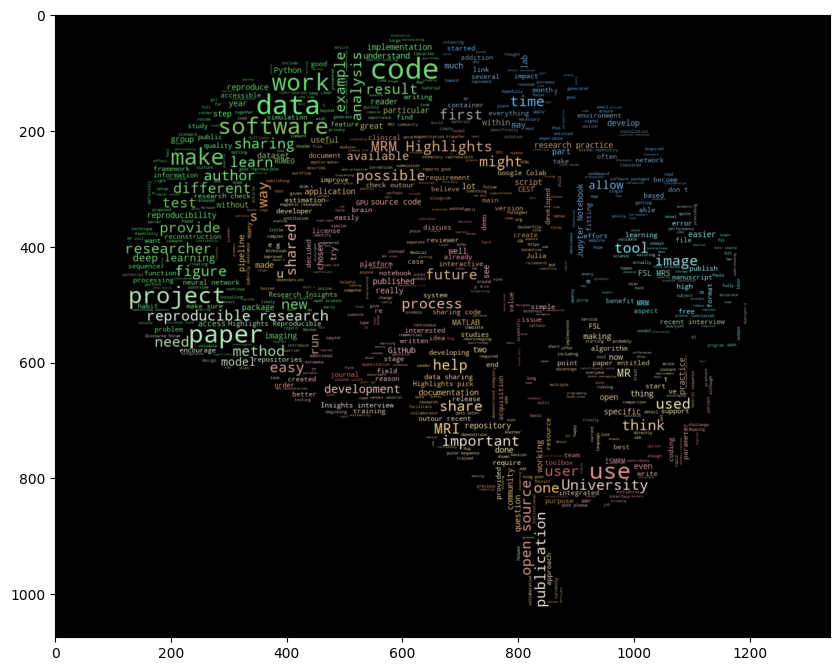

Figure 7 is a word cloud generated from the articles included in this review, highlighting the concepts and vocabulary that is driving reproducibility in MRI. As can be seen from the figure, the components of reproducibility in MRI research are multifaceted, integrating not just data and code, but also the analytical pipelines and hardware configurations. The shift towards comprehensive sharing is motivated both by a scientific ethic of transparency and the practical need for rigorous validation of complex methodologies [49,50].

However, this shift is not without challenges [51]. Variations in data acquisition and analysis methodologies limit cross-study comparisons. Sensitivity to software and hardware versions can impede direct reproducibility. Privacy concerns and data protection regulations can be barriers to data sharing, particularly with clinical images.

While challenges persist, steps are taken by individual researchers and institutions to prioritize reproducibility. Moving forward, the MRI community should work collectively to overcome barriers, institutionalize reproducible practices, and constructively address data sharing concerns to further the discipline’s progress.

The initiatives and tools identified in this review serve as a blueprint for future studies to replicate successful practices, safeguard against bias, and accelerate neuroscientific discovery. As MRI research continues to advance, upholding the principles of reproducibility will be essential to maintaining the integrity and translational potential of its findings. We also hope that our methodology in generating this review will pave the way for future studies that leverage large language models to create unique literature insights. In particular, we believe that the RRInsights GPT can serve as a blueprint for generating a scoping review [52] and inspire other scientists to experiment with the format of scientific publications in the age of AI.

- Stikov, N., Trzasko, J. D., & Bernstein, M. A. (2019). Reproducibility and the future of MRI research. Magn. Reson. Med., 82(6), 1981–1983.

- Cohan, A., Feldman, S., Beltagy, I., Downey, D., & Weld, D. S. (2020). SPECTER: Document-level Representation Learning using Citation-informed Transformers.

- McInnes, L., Healy, J., & Melville, J. (2018). UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction.

- Adebimpe, A., Bertolero, M., Dolui, S., Cieslak, M., Murtha, K., Baller, E. B., Boeve, B., Boxer, A., Butler, E. R., Cook, P., Colcombe, S., Covitz, S., Davatzikos, C., Davila, D. G., Elliott, M. A., Flounders, M. W., Franco, A. R., Gur, R. E., Gur, R. C., … Satterthwaite, T. D. (2022). ASLPrep: a platform for processing of arterial spin labeled MRI and quantification of regional brain perfusion. Nat. Methods, 19(6), 683–686.

- Tilea, B., Alberti, C., Adamsbaum, C., Armoogum, P., Oury, J. F., Cabrol, D., Sebag, G., Kalifa, G., & Garel, C. (2009). Cerebral biometry in fetal magnetic resonance imaging: new reference data. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol., 33(2), 173–181.